GX/Kernel Programming Guide

Introduction

QUICK START

1: Create a new workspace to build a GX/Kernel application:

$ cd $HOME/development

$ mkdir src

$ cd src

2: Clone the GX/Kernel repository:

$ git clone git://git.ghworks.org/gxkernel.git gxkernel

3: Create an application file …

$ nano myFirstApp.c

… and add the following code to make a simple application:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

DO_FOREVER

{

status = ALERT (SEC_10); // set timeout and wait

switch (status):

{

case TIMEOUT: // timeout occurred

printf("Success: timeout.");

default: // request failed

case FAILURE:

printf("Fault: system error.");

}

}

}

4: Edit the gxconfig.h file to match your hardware. The default settings are for the Motorola M68HC11 EVB evaluation board.

5: Run

$ maketo compile and link your example application with the GX/Kernel code and create a downloadable executable named main.hex.

6: The final output file, main.hex, can now be downloaded and tested on your hardware or emulator. Refer to the documentation provided with your target board, emulator or PROM programmer for specific instructions on downloading files.

7: Reset your target environment to run the myFirstApp example application. You should see the “Success: timeout.” message displayed every 10 seconds. You are now set up to build a full application.

The GX/Kernel features efficient and flexible real-time facilities that meet the demands of today’s hard-deadline, embedded systems.

While the run-time considerations are important, system development and maintenance are equally important. The complexity of real-time applications extends to all phases of the software life cycle. The GX/Kernel is designed to allow developers to work at a higher level of abstraction that translates to systems completed in less time and with fewer errors.

The following list summarizes the GX/Kernel features:

-

Preemptive Multitasking scheduler for real-time responsiveness.

-

Priority Scheduler Tasks may be prioritized by importance.

-

Multiple-instance Single-source code instance for multiple tasks.

-

Task Bank Switching Built-in facility supports bank switching.

-

Hard-deadline Deterministic scheduler.

-

Fault-tolerant Active fault detection and isolation.

-

Nested Interrupts Concurrent interrupts use a common stack.

-

C-language Interface High-level language support.

-

Rom-able Position-independent runtime code.

The following sections of this document describe how to install the GX/Kernel operating system software and cover the information needed to implement a multitasking application. This includes system definitions, an API reference, debugging tips, and information about resource utilization.

The GX/Kernel Model

The GX/Kernel model is a conceptual view of the software. Specifically, the model is concerned with system resource management.

For the GX/Kernel, the resources of interest are processing time and the allocation of program and data space memory to processing time intervals.

The task is the central concept for processor time management. By allocating task code memory space to a time segment, the kernel defines an entity that can be associated with time; and in real-time systems, time partitioning is an inherent requirement. Further, by assigning multiple task code memory spaces to different time segments, the GX/Kernel achieves multi-tasking.

The work actually done by a task is independent of the kernel, although, certain rules govern the construction of tasks, to achieve time segmentation.

Effectively, a task is an abstraction of time, which provides a time-associated entity that can be managed and referenced. In the GX/Kernel model, all functional references are with respect to tasks. These operations that may be performed within the context of a task are called primitives.

In addition to providing a mechanism for operating with tasks, primitives also provide higher abstractions for time and memory.

For time, primitives allow developers to design in terms of clock time, synchronization, and atomic operations. Collectively, these time-related primitives are called task coordination primitives.

For memory, primitives support abstractions such as queues, messages, and partitions. Generally, the GX/Kernel model supports static, rather than dynamic, memory. That is, all types of memory and their attributes are defined at design time. There is no dynamic memory allocation facility at run-time, except in a very specialized case. Such a memory model is better suited to hard-deadline applications, because system behavior becomes more predictable and simplified, with improved performance.

The Task Unit

This section discusses the concept and implementation of a task. It introduces the terminology associated with a task and discusses the kernel abstraction supported by the task.

In implementation terms, a task is a run-time instance of the source code. an example of a GX/Kernel task is shown below. The program gains control of the processor, executes application-specific logic, and explicitly releases control. A task uses coordination primitives to get and release processing time.

INT task_x ()

{

/* variable declarations */

INT status, msgid, msgsiz;

CHAR *msg_p;

/* task initialization */

if (task_x_init () == SUCCESS)

{

/* task definition */

DO_FOREVER

{

/* suspensive primitive */

status = RECV (&msgid, &msg_p, &msgsiz, SEC_1);

switch (status)

{

case SUCCESS: /* msg ready */

process_msg (msgid, msgsiz, msg_p);

break;

case TIMEOUT: /* no msg */

handle_timeout ();

break;

case FAILURE: /* fault */

default:

LOG_WARN (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_U + P0 + 0, NOT_USED);

break;

} /* end switch */

} /* end forever */

}

/* unrecoverable fault */

LOG_FATAL (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_U + P0 + 0, NOT_USED);

}

The Task and Its Environment

TASK DISCIPLINE

To design a system where a task is the unit of work, the task discipline imposed by the kernel must be understood. A main difference between operating systems is the task discipline.

In the GX/Kernel, once a task gains control of the processor, it runs to completion. That is, a task retains control until it explicitly releases control by calling a suspending primitive. This discipline supports tasks that run quickly and is consistent with the requirements of hard-deadline, real-time systems. The GX/Kernel is suited to those systems where only a small amount of time is needed to completely handle an event. Naturally, the granularity of an event becomes a design issue.

Care should be taken to only use kernel facilities to affect a task's behavior. For example, by using timing primitives to delay a task, instead of instructions that cause a task to busy-wait, other tasks are allowed to run while the task is waiting. Kernel fault management guards against tasks that don’t release control of the processor.

Although a task isn’t normally preempted by the kernel or another task, a task may be preempted by a hardware interrupt. This is transparent to the task, however, and processing always resumes with the interrupted task.

TASK ATTRIBUTES

Task capabilities and constraints can be modified for each task, individually, by changing a task's attributes.

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Priority | Each task may be assigned a priority level relative to other tasks. Tasks that have work pending and are ready to run are given processor control according to their priority. There are three priority levels. The first task ready at the highest priority level is the next task to run. |

| Instance | The GX/Kernel supports the concept of multiple-instance tasks. A task instance is a task that is "known" by the kernel at run-time. Usually, each instance is derived from a separate block of source code. With multiple instance tasks, however, more than one run-time instance may be from the same source code. This is useful for tasks that perform the same function on different entities, such as a task for each I/O channel or network link. Rather than having a single task maintain separate data for each entity, each task manages one set of data. These types of tasks are also more efficient because they don’t need to continually map an entity to its data or function. Care must be taken, however, in coding multiple instance tasks. Such tasks can’t declare and reference C language-type static data because each run-time instance references these same data. Dynamic data must be allocated by each task to get its own data space, usually at initialization time. |

| Memory area | Each task has its own stack and dynamic memory areas. The stack area is required. Any stack size may be defined, depending on expected stack usage. The stack is used by all subroutines called from the task, primitive calls, and interrupts that occur while in the TASK_STATE. Dynamic memory allocation is optional. If a task allocates dynamic memory, there are no restrictions on its use. Kernel fault management continually audits stack and dynamic memory to detect corruption. Corrupted memory causes the task to be deleted. While this may limit fault propagation and increase system availability, depending on the importance of the deleted task, it is likely that neighboring task memory is also corrupted. |

| Resident bank | The GX/Kernel supports hardware memory bank switching to extend the 64-kilobyte address limitation. Bank switching only applies to code space memory, however. If the code is located in ROM, then ROM bank switching is allowed and, if the code is located in RAM, then that part of RAM with code space may be switched. Bank switching isn’t supported for RAM data memory because this memory maintains the system context used by the kernel. The task unit is a natural unit of consideration for bank switching. This is because context switching already occurs at the task level, so context switching to another bank is no different than a normal kernel context switch. When a task is ready to run, the kernel determines the bank where the task resides, switches in the appropriate bank and resumes running the task. A task's resident bank is defined in the configuration file. The entry point of the user-provided bank switching procedure is also defined in the configuration file. The usual cautions apply in writing the bank switching procedure to be able to return to the original bank. The initialization stack area, in internal RAM, is available to preserve information across a bank switch. In addition, the kernel and any common routines must be located at the same location in all banks. Only task code area and some specialized routines may be bank-dependent. |

Task Identification and Creation

IDENTIFICATION

From a programming point of view, tasks are referenced by logical, symbolic names. This makes the system more maintainable and extensible. At initialization, a physical task name is assigned to each task, which is only used, directly, by the kernel. Applications never need to use the physical name, except as a primitive parameter, and then only to improve efficiency. The physical name may be gotten with the GETTID and GETMYTID primitives. This is usually done at task initialization because logical and physical task names never change.

CREATION

Tasks are created by the kernel at initialization from configuration file information. This information defines each task and its attributes, which the kernel uses to allocate task resources.

Once created, a task is usually never deleted. Two exceptions are 1) upon a system reset, and 2) when the kernel detected a critical fault while in the TASK state.

Kernel States

This section describes the states of the kernel, for overall resource management, and the states of a task, for task resource management.

State Descriptions

The kernel may be in any of four states, depending on the work to be done. State is used primarily to determine how memory resources are allocated.

| State | Description |

|---|---|

| INITIALIZATION | Immediately following a hardware or software reset, the kernel takes control of the processor. In this state, the only application programs that run are the hardware and software routines defined in the system configuration file. |

| TASK | If there is work for a task and the task assigned to the work is available, the kernel enters the TASK state. The intricacies of task-level processing are described in more detail in TASK STATES. |

| SUPERVISORY | In the SUPERVISORY state, resources are allocated from the systems resources, rather than task resources. This state may be entered when a hardware interrupt occurs during the TASK state. |

| MONITOR | When no task work or interrupt is pending, the kernel enters the MONITOR state and uses system resources. |

In the TASK and SUPERVISORY states, the watchdog (COP) monitors execution time. If the task execution time exceeds the watchdog period, the task is removed from the system and normal processing continues. The task is never scheduled to run again. If the execution time exceeds the watchdog period in the SUPERVISORY state, which occurs in an interrupt service routine, a system restart is initiated. The default watchdog period is 1.049 seconds and is set in the microcontroller's OPTION register.

TASK STATES

All tasks are put in a READY state at initialization. The first task in the task configuration table is the first task to run. Each task runs or initializes its local data areas until it calls a suspending primitive.

Task states change from READY to ACTIVE when work becomes available for the task. Real-time processing occurs when tasks are allocated processor time to perform work.

In the TASK state, with a task ACTIVE, the stack area is allocated from the task's local memory. A task runs until it calls a suspending primitive and there is no work to do or a higher priority task has work to do. When suspended, the task is in a WAIT state, waiting for a semaphore, event, message, or timer primitive. When a task resumes execution, processing begins at the point where the task was suspended, not necessarily at the task's entry point.

In addition to READY, ACTIVE, and WAIT states, a task may be in the DORMANT state. This occurs if a fault was detected by the kernel during the task's ACTIVE state. Once in the DORMANT state, the task can’t run again until the system is restarted; this prevents fault propagation.

NON-TASK STATES

The SUPERVISORY state is entered by a request to use common system resources. See the discussion below on handling interrupts, for more detailed information.

When there is no task work or interrupt pending, the kernel enters the MONITOR state. This switches the active stack to the system memory area, to be ready for an interrupt, and executes a STOP instruction. Processing resumes with the next interrupt; an interrupt always occurs under normal operating conditions with the Real Time Interrupt (RTII). To eventually return to the TASK state, an interrupt service routine must call a primitive that completes a task's wait condition.

Scheduling Policy

Tasks are prioritized in the system configuration table when the system is built. A task's priority never changes once the system is built, which assumes processing requirements are understood before run-time. With fixed task priorities, response times are predictable.

The next task to run is determined, whenever a task releases control of the processor, by calling a suspending primitive. At that time, the highest priority task in the READY state is run. When multiple, equal priority tasks are ready to run, the task that first became ready runs.

Tasks may be preempted by interrupts and the interrupt service routine may call a primitive that causes a waiting task to become READY. Processing always resumes with the interrupt task.

Initialization and Startup

The GX/Kernel does the basic hardware and software initialization needed to run the kernel in the target processor environment. It then automatically invokes initialization routines, provided by the developer, to initialize application-specific hardware and software.

The application-specific routines are the only initialization routines that need to be provided. Their entry points are specified in the configuration file when the system is built.

Also, configurable microcontroller parameters that need to be set at initialization are defined in the configuration file.

The kernel provides orderly initialization sequencing by initializing from lower to higher levels of abstraction. First, the hardware, then the kernel, and then application hardware and software are initialized; the idea is the hardware must be available for the kernel to run, and the hardware and kernel must be available for the application to run.

Entries in the configuration file provide hooks for the kernel to initialize application hardware and software. The kernel initializes application hardware before software.

At each step, the integrity of the supporting layer is confirmed before the next layer is initialized. If resources aren’t available for a layer to provide the necessary services, subsequent layers aren’t initialized.

Faults that occur before kernel resource allocation and initialization are complete are considered critical because the integrity of the system can’t be guaranteed. If a critical fault is detected, a STOP instruction is executed to prevent fault propagation.

Handling Interrupts

Conceptually, interrupt service routines are very similar to tasks in that they run as a result of an external stimulus that changes the context of the system. In the case of tasks, the stimuli may be messages, events, or semaphores, while in the case of an interrupt service routine, the stimulus is a hardware event detected by the microcontroller.

Task-related context switches that change resource allocation needs are managed by the kernel. However, there is no kernel to manage hardware-initiated context switches in the same way. Interrupt service routines must, therefore, explicitly interface with the tasks' kernel to coordinate resource allocation. A SUPERVISORY state is implemented in the kernel for interrupt management.

SUPERVISORY state is entered by calling the primitive, ENTER_SSTATE. In SUPERVISORY state, the interrupt uses the stack area from the system's memory area. Upon exiting from the interrupt, by calling EXIT_SSTATE, the interrupted task resumes at the point of interruption, again, using the task's memory area stack.

The kernel supports nested interrupts. That is, an interrupt may occur, and call ENTER_SSTATE, while another interrupt service routine is in progress. Control doesn’t return to the task until EXIT_SSTATE is called by the last interrupt service routine.

Tasks may become READY to run as a result of a primitive called by the interrupt service routine, which completes a task's WAITING primitive.

Kernel Primitives

This section discusses the concepts associated with primitives. A detailed description of each GX/Kernel primitive is found in Part 3.

GX/Kernel functions are called primitives because they are the basic function for interacting with tasks and requesting kernel services.

Primitives are called during task or interrupt service routine execution. While primitive code and static data are in the kernel code and data space, primitives use the calling task or interrupt service routine stack area.

Summary

GX/Kernel primitives are classified as follows. See the API documentation for more detailed information about each primitive.

| Classification | Primitive | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| TASK MANAGEMENT | GETTID | Get task identifier |

| GETMYTID | Get current task identifier | |

| TASK SYNCHRONIZATION | GET_CRID | Get critical region identifier |

| ENTER_CR | Enter critical region; semaphore | |

| EXIT_CR | Exit critical region | |

| ENTER_SCR | Enter supervisory critical region | |

| EXIT_SCR | Exit supervisory critical region | |

| SIGNAL | Signal event occurrence | |

| WAIT | Wait for event occurrence | |

| SEND | Send message | |

| RECV | Receive message | |

| TIMER SERVICES | ALERT | Alert after time interval |

| GETTIK | Get current timer value | |

| QUEUE MANAGEMENT | Q_GETID | Get linked list identifier |

| Q_CLEAR | Initialize linked list | |

| Q_GET | Get item from linked list | |

| Q_PUT | Add item to linked list | |

| MEMORY MANAGEMENT | LOCATE_MEM | Get task dynamic memory |

| FAULT MANAGEMENT | [LOG_WARN](#log_warn) | Report non-critical fault |

| [LOG_FATAL](#log_fatal) | Report critical fault; initiate recovery | |

| INTERRUPT MANAGEMENT | ENTER_SSTATE | Enter supervisory state |

| EXIT_SSTATE | Exit supervisory state |

Suspensive Primitives

There are two types of primitives. Those that may cause a task to be preempted are called suspending primitives, and those that return to the caller without preemption and are called non-underline suspending primitives. The suspending primitives are,

| Primitive | Suspending Condition |

|---|---|

| ENTER_CR | Critical region isn’t available. Unblocking primitive: EXIT_CR or timeout |

| RECV | No message is pending for the task. Unblocking primitive: SEND or timeout |

| WAIT | No event is pending for the task for requested event condition. Unblocking primitive: SIGNAL or timeout |

The suspending primitives have complementing primitives which, when called from another task or interrupt service routine, cause the suspended task to resume. A task resumes when the suspending condition is satisfied.

Suspending primitives may not be called from an interrupt service routine because an interrupt may not be suspended by the kernel. Suspension supports real-time applications at the task level.

While tasks may be prioritized, primitives don’t have a priority attribute. For example, there is no priority assigned to messages for the SEND and RECV primitives. All prioritization is considered with respect to tasks.

System Reliability

This section discusses the reliability issues associated with embedded, real-time systems.

GX/Kernel features that promote the development of reliable systems are also presented.

Reliability Issues

Real-time systems are particularly error-prone because of their inherent complexity; as complexity increases the probability of errors also increases.

This problem is compounded by the requirement for embedded systems to operate without intervention, possibly in the presence of errors.

Systems may be classified as fault-tolerant or fault-intolerant. Fault-tolerant systems are characterized by anticipating that all errors can’t be removed before run-time, and mechanisms are provided to detect and handle faults when they do occur. Complex, real-time systems, usually, can’t be tested adequately to guarantee that no faults occur. Fault intolerant systems, on the other hand, assume that the system is sufficiently tested, no faults occur, and no fault handling is provided.

The GX/Kernel is a fault-tolerant. By implementing fault management, the GX/Kernel achieves the objectives of increased system availability and assures algorithm correctness.

Reliability by Design

The GX/Kernel allows reliability to be designed into a system.

One method of fault management that is implemented in the system design is software layering. A layered system allows it to be viewed in smaller, logically related, less complex segments. This makes the design more manageable and, by extension, more reliable. Layering is also a facility for the isolation of faults. If a fault can be isolated to a layer, then only that layer needs to be recovered, and system availability is increased.

The kernel, itself, may be considered a single layer. However, because it is the most dependent layer faults detected in the kernel usually require complete system recovery. The kernel may not need to be recovered if faults are detected in an application layer.

The GX/Kernel supports reliable system design by its built-in fault management policies and by providing mechanisms for applications to interface to the fault management system. These policies and mechanisms are described in the sections, below.

Fault Management

Fault management has three aspects; 1) fault detection, 2) fault handling and reporting, and 3) fault recovery.

The kernel uses its fault analysis area for fault management. These data are described in detail in a separate section.

FAULT DETECTION

B y active fault detection, the kernel can reduce fault propagation. This is the primary mechanism that supports the fault-tolerant objectives. The following fault detection methods are used by the GX/Kernel.

Memory Audits

The GX/Kernel partitions and classifies memory for fault management. If the type of memory is known, the kernel can verify that the data is consistent with the memory type. While this method doesn’t guarantee fault detection, common types of memory corruption are detectable. System and task stacks, kernel data structures, and kernel structures, such as queues, in the application memory area are continuously audited.

Guarded Primitive Access

Whenever a primitive is called, the kernel verifies that it is a valid primitive, that the parameters are consistent and within kernel-defined limits, and that resources are available.

Software Watchdog

The hardware watchdog (COP) is used to detect tasks and interrupt service

routines that keep control of the processor for longer than the watchdog period.

This is an indication of faulty algorithm execution.

The above fault detection methods are used at run-time. To reduce development time by detecting errors early in the process, system build tools are part of GX/Kernel fault management. This supports the notion that faults detected early in the development cycle are less expensive to correct.

Fault detection before run-time has the added benefit of freeing the kernel from some fault detection at run-time, resulting in a more efficient kernel.

The following fault detection methods are used during implementation.

Primitive Declaration

The macro declaration of the primitive interface allows most assemblers and compilers to detect reference and parameter errors in the primitive call.

System Build Utility

This is the primary tool for fault management before run-time that relates directly to the kernel. The system build utility, described in detail in a separate section, tests for overall resource availability and data consistency.

The high-level language interface allows applications to be implemented with the probability of fewer errors.

FAULT HANDLING AND RECOVERY

Once faults are detected they must be handled to achieve fault tolerance. A completely handled fault includes a determination of fault severity, reporting and logging the fault, and initiating recovery action. Recovery action depends on the type and severity of the fault.

Kernel Fault Handling

Kernel-detected faults are only acted on if they are determined to be critical to system operation. Otherwise, the fault is only reported and logged.

Fault classification, either critical or acceptable, depends on the kernel state and the scope of the data if it is a data-related fault. Acceptable faults, from the kernel's point of view, are those that are limited to a single task. Such faults occur in the TASK state or in a task's stack or dynamic data. Faults in any other kernel state are classified as critical.

For acceptable faults, the kernel simply deletes the affected task, so the fault isn’t repeated or propagated. The fault is reported to the fault handling task if one is defined. It is left to the application to determine the impact of the deleted task and take appropriate recovery action.

For critical faults, the kernel determines that system integrity can’t be guaranteed. The kernel, therefore, reports the fault, then initiates a kernel restart. The restart causes all tasks to be restarted. The cause of the restart is available in the fault analysis area.

Application Fault Handling

Application-detected faults are independent of the kernel. Their classification and recovery action depends on the application. Applications use kernel primitives to report the fault and initiate recovery.

The LOG_WARN primitive is used to report non-critical faults. This is useful for noteworthy faults that don’t affect system operation, and for check-pointing during debugging. The fault is only reported and logged; no recovery is initiated by the kernel.

The LOG_FATAL primitive is used to report faults the application determines adversely affect system operation. The kernel reports the fault and initiates recovery by restarting the kernel, which also restarts the tasks.

Both LOG_WARN and LOG_FATAL cause fault-related information to be logged in the kernel's fault analysis area. This information is available at run-time to report the fault and is useful during debugging to determine the cause of the fault.

Optionally, the fault may be reported to a fault-handling task. The task name must first be defined in the configuration file. This allows the application to take application-dependent recovery action.

For primitive access, the kernel detects some classes of errors before a fault occurs. An example is primitive parameter errors. The kernel reports these faults in the status returned by the primitive. The kernel always returns a status to a primitive call. It is the responsibility of the application to check the return value and take the appropriate action.

Installation and Integration

The Release Package

The release package contains all required G/Kernel software, the system build utility, and samples for tasks, configuration files, and development tools.

The G/Kernel software is compatible with Archimedes development tools. Source code and include file syntax are also compatible with the Archimedes assembler, although minor editing changes allow the software to be used in other development environments.

Release Directories

The release contains the G/Kernel code and utility software in the following directories.

/src

This directory contains the GX/Kernel source files, including the gxconfig.h file for configuring your system.

/inc

This directory contains the following include files for assembly and C language source code. These files contain the declarations needed to interface to the G/Kernel.

| Assembly | C language | Contents |

|---|---|---|

| gki-l.inc | gki-l.h | Global literals |

| gki-t.h | Global types | |

| gki-k-l.inc | gki-k-l.h | Kernel literals |

| gki-k-m.inc | gki-k-m.h | Kernel macros |

| gki-k-e.inc | gki-k-e.h | Kernel externals |

/obj

This directory contains the following relocatable object files compatible with the Archimedes M68HC11 linker. To create object files compatible with other linkers, the source code must be assembled with the target assembler.

/tools

The /tools directory has the make file

to build the target system configuration file.

/examples

Example files are provided for first-time users of the G/Kernel. These files provide direction for integrating the kernel into a system.

| Filename | Description |

|---|---|

| gxk000.xcl | This is a linker command file. It is useful for showing the memory assignments defined during linking and for the inclusion and ordering of G/Kernel files. |

| gkc-stt.asm | This is an example configuration source file, which may be created with a text editor or by using the sysbld.sh utility. |

| gkc-iv.asm | This is the default interrupt vector table distributed with the kernel. This file needs to be changed to support the interrupts used by an application; those interrupts used by the kernel shouldn’t be changed, however. |

Kernel Installation

Install G/Kernel with the following steps:

$ cd $HOME/development

$ mkdir src

$ cd src

- Create a new location to build a G/Kernel application:

$ git clone git://git.ghworks.org/gxkernel.git gxkernel

- Clone the G/Kernel repository:

The files needed to build and debug an application are in the following directories:

| Directory | Description |

|---|---|

| /examples | Development examples |

| /inc | G/Kernel include files |

| /obj | G/Kernel object files |

| /src | G/Kernel source files |

| /tools | System build utility |

Kernel Integration

A number of simple steps are needed to integrate the kernel and application. These steps may vary, depending on the development environment and tools used.

If the Archimedes tool set is used, only the object files are needed, to link the G/Kernel with the rest of the system.

If other tools are used, the source code files need to be edited to be compatible with the assembler used. Generally, this only means changing assembler DIRECTIVE statements to those recognized by the assembler. All include files, both those used by the kernel and those used to interface to the kernel, may also need to be edited.

The C language include files don’t need to be changed, because no vendor-dependent constructs or library functions are used.

-

Assemble the kernel source code files; this requires the include files in the source code directory and the /inc directory.

The include files are provided in assembly and C language source code. They must be declared in the order shown in the example to the right, which is done by including the gxos.h and gxos.inc include files.

It is required that you set the correct include file pathname in the assembler and compiler command lines, or in the source code declarations.

-

Edit and assemble the interrupt vector table source code file, gkc-iv, to include the interrupt vectors used by the application.

If the application uses interrupts, the default interrupt vector table, gkc-iv, needs to be changed to add the entry points for application interrupt service routines.

Care should be taken that interrupt vectors used by the kernel aren’t modified. See Interrupt Vectors.

-

Create and assemble the system configuration source code file, using either a text editor or the sysbld.sh utility.

The system configuration file provides the link between the kernel and application. It is a program source file, which needs to be created then assembled. It may be created using a text editor or the sysbld.sh utility. The example configuration file may serve as a template for a new file.

-

Create a linker command file that includes the kernel object files, as shown in the example gxk000.xcl file.

-

Link the system to produce a binary or hex file for the target hardware. This step is the same as for a system that doesn’t include the G/Kernel.

After all kernel files have been edited and successfully assembled, the kernel object files may be linked with your application source files.

Language Considerations

The G/Kernel implementation allows it to be portable across different development environments. This is done by using generic language features and constructs defined by well-established standards. Constructs and features particular to a specific vendor are avoided.

The assembly language instruction syntax follows that defined in the Motorola technical documents for the M68HC11. However, the assembly language source code also contains directives for such things as symbols, macro definitions, and memory location specifications. For these directives, Archimedes-defined constructs have been used. However, their function is common across most assemblers and the directive may be replaced by the corresponding one for the assembler in use.

No compiler vendor-dependent externals, including library functions, are referenced. All external references are resolved within the kernel, with links to the application through the configuration file.

Many compilers require special initialization code and library functions, depending on how the C code is written. If the application invokes these, they must be specified in the linker command file.

Because the kernel manages the initialization sequence, any

compiler-required initialization must be done in the software

initialization procedure, which is accessed through the configuration

file entry point, sw-init-ep. For example, a procedure required by

some compilers to initialize constant data at run-time provides this

function. Alternatively, initialize the data in an assembly language

file, which eliminates the need for compiler-specific procedures and

makes the software portable to other compilers.

If bank switching is used to extend the addressing limitation, bank switching must be done through the kernel. This supports the abstraction that the kernel manages system resources and memory is a resource. Language support for bank switching can’t be used in the kernel environment.

Hardware Interface

This section discusses the hardware interface as it applies to the G/Kernel. Refer to Motorola technical documentation for a detailed description of the M68HC11.

M68HC11 Configuration

INTERNAL RAM

The kernel uses the microcontroller internal RAM for its primary control data. This allows the kernel to take advantage of the direct addressing mode for memory reference instructions. The result is increased performance because most of the program execution occurs within the kernel.

After initialization, some of this area is made available to the application. See the section on memory layout for a description of internal RAM.

INTERNAL REGISTERS

Only those internal registers listed below are used by the kernel. All others are available for the application.

The kernel guarantees that the microcontroller time-protected registers are initialized within the required time limit.

The 64-byte register block may be located on any 4K boundary. Default register settings may be used or other values may be used for special application requirements. The settings are defined in the configuration file.

| Register | Address | Default Value | Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPRIO | 03CH | 07H | This sets the real-time interrupt as the highest priority interrupt source. This is to assure the accuracy of the kernel timer services. |

| INIT | 03DH | 01H | This positions the 64-byte internal register block at address 1000H. |

| OPTION | 039H | 03H | This sets the watchdog (COP) timeout rate to 1.049 seconds, for an 8MHz crystal. The watchdog is pulsed by the kernel whenever a task switch occurs, or periodically if there is no task work pending. This means that a task must not retain control of the processor for greater than the watchdog timeout period. |

| TMSK2 | 024H | 03H | This sets the timer prescale factor to 16 for a real-time interrupt rate of 32.77 milliseconds. |

INTERRUPT VECTORS

The kernel handles the following interrupt vectors:

| IRQ | Address | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| RTII | FFF0H | The real-time clock interrupt supports kernel timer services. |

| SWI | FFF6H | The software interrupt (TRAP) is used for the application interface to the kernel. |

| RESET | FFFEH | The reset interrupt is used to vector execution to the start of the kernel initialization sequence. |

If the default interrupt vector table is used, the following interrupts report a fatal fault then vector to the start of the kernel initialization sequence, the same as a RESET interrupt:

| IRQ | Address | Usage |

|---|---|---|

| OPCODE | FFF8H | Illegal opcode detected. |

| COP | FFFAH | Watchdog timeout. |

| CME | FFFCH | Clock monitor failure. |

The default interrupt vector table causes all other interrupts to be reported as warning faults, then returns from the interrupt.

Hardware Configuration

The G/Kernel requires that the microcontroller be configured for Expanded Multiplexed Operation (MODE 1).

Memory locations may be configured for any location allowed by the microcontroller. An exception is internal RAM, which must always be located at address 0000H.

All microcontroller interfaces not described above are available to the application, with no restriction on their use by the kernel.

Any combination of RAM and ROM options is allowed. The kernel code is ROMable.

The kernel supports up to four memory banks for task code space. These may be either RAM or ROM memory.

The kernel automatically switches in the bank where the task code resides by calling the user-provided bank switching routine. The entry point for this routine is defined in the configuration file.

Global Definitions

This section describes the GX/Kernel interface conventions. These conventions have been defined to give a consistent interface, which makes application software easier to implement and maintain.

Primitive Access

The primitive interface to the GX/Kernel is invoked as an assembly or C language subroutine call. Macros, defined in include files gki-k-m.h and gki-k-m.inc implement the actual access to the kernel.

All kernel primitives return a function status. This is the status of

the execution of the algorithm for the primitive; either SUCCESS,

FAILURE, or a specialized meaning, such as TIMEOUT. No data associated with the

primitive are ever returned as a status. Data are passed and returned as

parameters.

Literals Used with Primitives

Include files provide a common, portable interface to the GX/Kernel. Include files gki-l.h, gki-l.inc, gki-k-l.h and gki-k-l.inc contain the literals used with the kernel primitives described in this section. These include files that might be changed to adapt the kernel to the application.

These literals provide a method to reference kernel attributes symbolically. This higher level of abstraction makes the interface more maintainable and portable.

Example using GX/Kernel literals:

status = ALERT (SEC_10); // timer literal: SEC_10

switch (status):

{

case TIMEOUT: // return status literal: TIMEOUT

handle_timeout();

default:

case FAILURE: // return status literal: FAILURE

handle_error();

}

General

| Literal | Description |

|---|---|

TRUE |

General literal for TRUE conditional. |

FALSE |

General literal for FALSE conditional. |

DO_FOREVER |

This is used within a task to define the start of the main task execution loop. |

DO_NOTHING |

A statement place-holder, which generates no code. |

INV_ADDR |

This literal is used to set pointer variables to an invalid address, which may be used for fault detection. |

NOT_USED |

This is a parameter literal to indicate a parameter isn’t used or has no significance. |

SUCCESS |

This value is returned by primitives to indicate no errors occurred. |

FAILURE |

If an error occurred during primitive execution, a FAILURE status is returned. |

TIMEOUT |

This literal is returned by primitives to indicate a timeout condition occurred while waiting for the requested operation. |

NO_TOUT |

If no timeout is desired, this literal is used for the time-specification parameter. |

Task Attributes

| Literal | Description |

|---|---|

MAX_TSK |

For task management operations, this defines the maximum number of task instances, including multiple-instance tasks, that may be referenced. The range is 0 to 63. |

MAX_TNAME |

For task management operations, this defines the limit for task names. The range is 0 to 63. |

INV_TNAME |

Invalid task name indication. |

INV_TID |

Invalid task identifier. |

STKSIZ_L |

Stack sizes: large |

STKSIZ_M |

Stack sizes: medium |

STKSIZ_S |

Stack sizes: small |

MEMSIZ_L |

Dynamic memory sizes: large |

MEMSIZ_M |

Dynamic memory sizes: medium |

MEMSIZ_S |

Dynamic memory sizes: small |

PRI_HIGH |

Task relative priorities: high |

PRI_NORM |

Task relative priorities: normal |

PRI_NONE |

Task relative priorities: none |

BANK_0 through BANK_3 |

Task resident bank location: bank 0 through bank 3 |

Queue Management

| Literal | Description |

|---|---|

MAX_QUE |

For queue management operations, this defines the maximum number of queues that may be referenced. The range is 0 to 255. |

INV_QNAME |

Invalid queue name reference. |

INV_QID |

Invalid queue identifier. |

Q_FULL |

Queue is full indication. |

Q_EMPTY |

Queue is empty indication. |

Semaphore Management

| Literal | Description |

|---|---|

MAX_SEM |

For semaphore-related operations, this defines the maximum number of semaphores that may be referenced. The range is 0 to 255. |

INV_SEMNAME |

Invalid semaphore name reference. |

INV_SEMID |

Invalid semaphore identifier. |

Event Management

| Literal | Description |

|---|---|

EVT_OR |

Conditionally wait for any event specified. |

EVT_AND |

Conditionally wait for all events specified. |

EVT_0 through EVT_15 |

Specific event identifiers: event number 0 to event number 15, the maximum number of events. These symbolic names may be replaced by names meaningful to the application. |

Timer Management

The following time interval literals are defined:

| Literal | Description |

|---|---|

MS_100 |

100 milliseconds |

MS_500 |

500 milliseconds |

SEC_1 |

One second |

SEC_10 |

Ten seconds |

MIN_1 |

One minute |

MIN_10 |

Ten minutes |

HR_1 |

One hour |

LOG_FATAL example:

LOG_FATAL (LY_3 + SS_0 + LV_L + P2 + 3, NOT_USED)

Fault Management

When used as the error location parameter with the LOG_FATAL and LOG_WARN primitives these literals have the following bit position significance:

| Bit Position | Description |

|---|---|

| 15 | reserved |

| 14‑12 | layer identifier |

| 11‑10 | subsystem identifier |

| 9‑8 | level identifier |

| 7‑4 | procedure identifier |

| 3‑0 | fault identifier |

Here is an example of how the literals may be used with the fault management primitives. The example reports the third fault in layer 3, subsystem 0, level 2, and procedure 2.

The error location is logged in the Fault Analysis Area.

| Literal | Description |

|---|---|

LY_0 through LY_7 |

System layer: 0 to 7 |

SS_0 through SS_3 |

Layer subsystem: 0 to 3 |

LV_C |

Procedure/level: common |

LV_L |

Procedure/level: lower |

LV_M |

Procedure/level: middle |

LV_U |

Procedure/level: upper |

P0 through P15 |

Location in procedure/level: 1 to 15 |

Debugging

The data structures described here are useful for debugging to get visibility into kernel and task states.

These data are used exclusively by the kernel and never need to be referenced by application software.

Refer to the section on memory layout for the location of these data, which are shown below as C- language structures.

Kernel Control Data

typedef struct

{

FAA faa; // fault analysis area

CHAR monstk[SSTK_SIZ]; // initialization stack

QCB sk_q_pr0; // task scheduler queues

QCB sk_q_pr1;

QCB sk_q_pr2;

QCB msg_free_q; // free message queue

CHAR istate; // kernel state

TCB *curtsk; // currently active task

TCB *flttsk; // fault management task

INT task_cnt; // total number of tasks

WORD clktik_cnt; // continuous timer counter

CHAR clktik_skip; // timer rate adjustment

CHAR curbnk; // currently active bank

TCB *tcbblk_p; // locations: task control blocks

QCB *queblk_p; // queue resource blocks

CHAR *semblk_p; // semaphore block

MSG_D *msgblk_p; // message resource block

CHAR *clkblk_p; // interval timer block

CHAR *dmemblk_p; // memory allocation ctrl.

CHAR *sstktop_p; // top of supervisor stack

} KDD;

(data

structure

element

descriptions

to be

provided)

Task Control Block

These data describe a task instance.

typedef struct

{

BYTE *tcb_link; // linked list pointer

CHAR tname; // task name

CHAR tattr; // task-type data marker

INT (*ent_pt)(); // task entry point

QCB *priority_qp; // task priority

CHAR *stktop; // top of task stack

CHAR *stkend; // end of task stack

CHAR *stk_p; // current stack pointer

QCB w_que; // task wait queue

CHAR state; // current task state

EVT_D evt; // task event management

QCB msg_q; // task message list

} TCB;

(data

structure

element

descriptions

to be

provided)

Task Queue Control Block

These data describe the state of a task message queue.

typedef struct

{

CHAR q_mark; // queue-type data marker

CHAR q_sem; // queue semaphore

BYTE **head; // head item pointer

BYTE **tail; // tail item pointer

} QCB;

(data

structure

element

descriptions

to be

provided)

Task Event Descriptor

These data describe the state of events associated with a task.

typedef struct

{

CHAR logic; // event request condition

WORD evt_wt; // pending event map

WORD evt_sig; // posted event map

} EVT_D;

(data

structure

element

descriptions

to be

provided)

Task Message Descriptor

These data describe the task message state.

typedef struct

{

BYTE *msglnk; // message link

CHAR msgmrk; // message-type data marker

INT msgid; // message identification

INT msgsiz; // message size

CHAR *msg_p; // message location

} MSG_D;

(data

structure

element

descriptions

to be

provided)

Fault Analysis Area

This data area is used to log fault information reported by the LOG_FATAL and LOG_WARN primitives.

Its content reflects the system state when the fault was reported.

For the LOG_WARN primitive, only fault_loc and fault_qual data are logged.

Task-related data isn’t logged if no task is active when the fault is reported.

Fault Analysis Area

typedef struct

{

CHAR r_A; // processor registers: A

CHAR r_B; // B

WORD r_IX; // IX

WORD r_IY; // IY

WORD sp; // SP

WORD pc; // PC

CHAR cc; // CC

CHAR istate; // kernel state

CHAR *curtcb_p; // active task

CHAR curtcb[32]; // active task control block

CHAR ustk[16]; // task stack

CHAR sstk[16]; // supervisor stack

WORD fault_loc; // fault location

WORD fault_qual; // fault qualifier data

} FAA;

(data

structure

element

descriptions

to be

provided)

Memory Allocation

One of the resources managed by the GX/Kernel is memory. This section presents the GX/Kernel view of memory and the management policies.

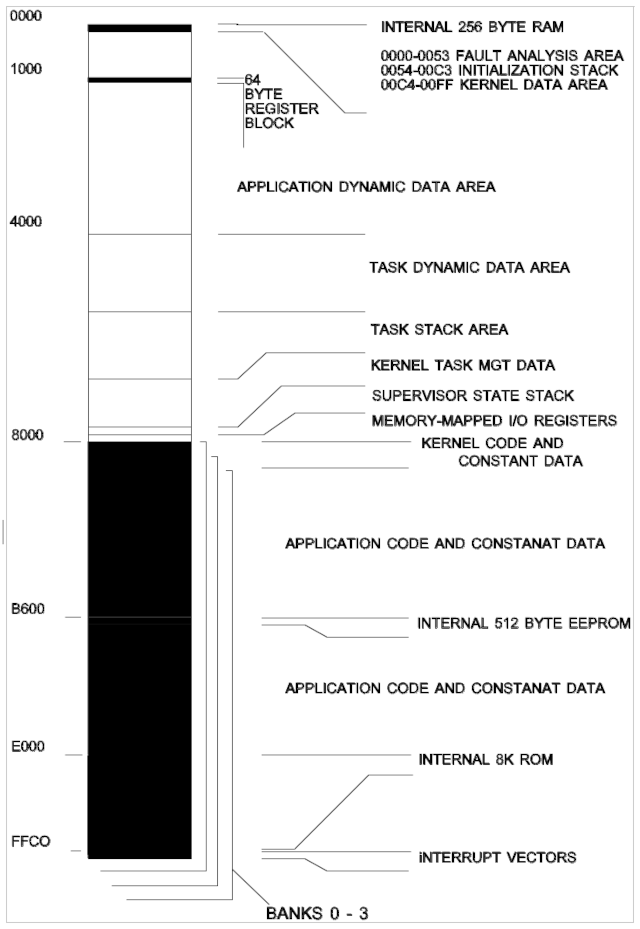

The following figure shows a typical memory map for an MC68HC11A8 version microcontroller with internal RAM, ROM, and EEPROM. The map can be applied to other versions by accounting for the different types of memory available and their location.

The GX/Kernel, itself, doesn’t place restrictions on memory type or location, except for the 256 bytes from locations 0000H to 00FFH. This is the only memory used by the kernel that is required to be at a fixed location.

The kernel code may be located in RAM or ROM.

The example shows a system with external RAM beginning at address 0000H, and external ROM or RAM beginning at address 8000H, for the full 64K address space. Memory banks, up to a maximum of four, are shown in the upper half of the address space.

Memory partitions

INTERNAL 256-BYTE RAM

This area is used by the kernel for fault management and control information. Locations 0054H to 00C3H are used as the stack area during initialization. Once the task state is entered, these locations are available to the application. However, these data aren’t preserved on a system restart.

64-BYTE REGISTER BLOCK

These control registers are described in the Motorola M68HC11 reference manuals. This block may be located on any 4K byte boundary. The kernel uses configuration file data to set the registers' location.

APPLICATION DYNAMIC DATA AREA

This area is memory, which isn’t specifically dedicated to a task. For example, database memory or abstract data type instances.

The kernel provides no protection mechanisms for accessing this memory.

This memory isn’t accessed by the kernel, except during the initialization RAM test.

TASK DYNAMIC DATA AREA

This area is divided into partitions, each of which is dedicated to a specific task.

The kernel dynamically allocates blocks of this memory to tasks at initialization. The size is defined in the configuration file. The kernel never makes the location available to a task that doesn’t "own" the partition.

The kernel never accesses this area, except during the initialization RAM test.

TASK STACK AREA

Task stacks are located in this area. There is a separate area for each task.

The kernel also uses this area to save the task context when a task is suspended.

Interrupts also use the task stack area, unless the ENTER_ISTATE primitive is called by the interrupt service routine.

KERNEL TASK MANAGEMENT DATA

Kernel and task RAM requirements are application-dependent and are derived from configuration file entries. The following values are used to determine the amount of RAM needed for the kernel.

256 bytes for the kernel and supervisory state stack

512 bytes for kernel time management services

6 bytes for kernel message services.

TOTAL FIXED RAM NEEDED: 774 bytes

Variable memory sizes are calculated, based on the number of tasks and resources.

6 bytes are needed for each queue resource

8 bytes are needed for each semaphore resource

9 bytes are needed for each message buffer resource

32 bytes are needed for management of each task

MINIMUM RAM NEEDED:

(at least one task and no resources defined)

806 bytes

SUPERVISOR STATE STACK

This is the common stack area for the kernel supervisor state and for interrupts.

Use of this area for nested interrupts, by calling ENTER_ISTATE from the interrupt service routine, reducing task stack requirements.

MEMORY-MAPPED I/O REGISTERS

This memory type may or may not be present, depending on the hardware design.

It includes registers used to access peripheral devices, external to the microcontroller.

KERNEL CODE AND CONSTANT DATA

The kernel needs less than 2500 bytes for code space, located either in RAM or ROM.

If multiple banks are used, an instance of the kernel code must reside in each bank and at the same location.

This area is checksummed at initialization, to verify kernel integrity.

APPLICATION CODE AND CONSTANT DATA

This area is for non-kernel code and constant data.

If code or data are shared by tasks in different banks, an instance of the shared code and data must reside in the same location in each bank.

INTERNAL 512-BYTE EEPROM

This internal EEPROM is available to applications, as described in Motorola technical documentation.

This memory isn’t used by the kernel.

INTERNAL 8K ROM

This internal ROM is available to applications, as described in Motorola technical documentation.

This memory isn’t used by the kernel.

INTERRUPT VECTORS

These are the hardware interrupt vector registers, as described in Motorola technical documentation. Only the real-time interrupt (RTII), software interrupt (SWI), and RESET vector interrupt are reserved for the kernel.

Task Memory Allocation

Tasks require code, stack, and, optionally, dynamic memory areas.

Dynamic memory is provided as a means of partitioning memory for the exclusive use of the task. How this memory is allocated and used by the task at run-time, is an issue for application design. This memory isn’t used by the kernel or other tasks, although a task may inform other tasks of the location of its dynamic memory. This memory is never released.

The sizes of each task's stack and dynamic memory areas are defined in the configuration file. However, the locations of task stack and dynamic memory are determined at initialization. The primitive, LOCATE_MEM, is used to effectively allocate dynamic memory.

CPU Utilization

To estimate system performance, this section gives reference times for various GX/Kernel facilities. All times are for an 8 MHz crystal (500 nanosecond instruction cycle time).

Context Switch Timing

The time needed to switch from a task that has released control of the processor to the next ready task is 28 microseconds.

This includes the time needed for data integrity checks and to pulse the watchdog.

This number applies if the next task to run is a high-priority task. For each lower priority level, an additional six microseconds is needed.

When an interrupt occurs, the time needed to switch to the interrupt service routine, regardless of whether the kernel is in the task or supervisor state, is 13 to 44 microseconds. The variance depends on the instruction in progress when the interrupt occurred.

This timing includes the primitive call to ENTER_SSTATE (the interrupt service routine is considered entered immediately upon return from the primitive call) and is slightly less if the kernel is already in supervisor state.

Primitive Timing

Fifteen microseconds are needed to access any primitive, and most primitives complete in less than 50 microseconds.

However, a look at the messaging and event management primitives gives an indication of actual, useful work capability for those primitives.

The time between the call to SEND a message and when the RECV call is completed, for two high-priority tasks, is 476 microseconds, which is about 2,100 messages per second.

For each lower task priority level, about six microseconds more is needed to send and receive a message. Messages don’t have a priority.

Similarly, the time between the call to SIGNAL an event and when the WAIT for the event is completed, for two high-priority tasks, is 422 microseconds. This is about 2,369 events per second. As with messaging, about six microseconds is added for each lower task priority level.

API Reference

This section gives a detailed description of the GX/Kernel API primitives used to invoke kernel services.

For each primitive, a functional description is given along with operational considerations particular to the primitive. This is followed by a description of the actual subroutine call.

The description shows the C and assembly language macro interface with the required parameters and return value. All parameters are required, although, parameters not applicable for a particular call contain a place-holding literal such as NOT_USED.

For the assembly language interface, all registers are preserved, except the D register, which returns the primitive status. The returned D-register status has the same meaning as the C- language interface status.

For both C and assembly language, parameters shown in upper case are literal constants, while those in lowercase are memory address references.

ALERT

Request Wakeup after Time Interval

SYNTAX

status = ALERT (tout_val);

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

status = ALERT (SEC_10); // set 10-second timer and wait

switch (status):

{

case TIMEOUT: // timeout occurred

handle_timeout();

break;

default: // request failed

case FAILURE:

LOG_WARN (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_L + P0 + 0, NOT_USED);

}

}

DESCRIPTION

Request for the task to be signaled after a specified amount of time has elapsed.

This is a suspending primitive.

When the timeout occurs, the task is scheduled to run according to its assigned priority.

There is no provision to cancel an alert request before the timeout occurs.

If NO_TOUT is requested, this primitive has no effect, and the task continues as the active task.

The time interval is associated with the real-time clock interrupt rate and is accurate to within one clock increment.

The alert request applies to the currently active task and may not be called from an ISR.

The time interval parameter is expressed in 100-millisecond units. The minimum time interval that may be requested is 100-milliseconds and the maximum is 6553.5 seconds. Accuracy is +/- 100-milliseconds.

PARAMETERS

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| tout_val | INT | Elapsed time value in 100-millisecond increments. |

RETURN

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| TIMEOUT | tout_val requested time has expired. |

| FAILURE | Unable to handle alert request. |

ENTER_CR

Get Access to Resource

SYNTAX

status = ENTER_CR (cr_id);

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

BYTE app_cr;

// get critical region ID defined in config file

if (GET_CRID (RESOURCE_A, &app_cr) == SUCCESS)

{

status = ENTER_CR (&app_cr);

switch (status):

{

case SUCCESS: // region acquired

process_resource();

status = EXIT_CR (&app_cr); // release region

break;

default:

case FAILURE: // invalid cr ID

LOG_WARN (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_L + P0 + 0, NOT_USED);

}

}

}

DESCRIPTION

This primitive provides for synchronization on a user-defined resource using a semaphore and guarantees mutually exclusive access to a resource.

The resource id must first be gotten using the CR_GETID primitive.

Resource access is managed by a semaphore, and tasks are queued to the semaphore on a first-come-first-serve basis. If the resource isn’t locked by another task, the resource is locked and the calling task continues as the active task. If the resource isn’t available, the calling task is suspended. The task remains suspended until all previous tasks have released exclusive access to the resource.

If the current task has already locked the resource, this primitive has no effect, although an error status is returned.

This primitive may not be called from an interrupt service routine.

A resource is released by the EXIT_CR primitive.

PARAMETERS

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cr_id | BYTE* | Resource id |

RETURN

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| SUCCESS | Access granted and resource locked. |

| FAILURE | Invalid resource id or task has already acquired resource. |

ENTER_SCR

Get Exclusive Access to Processor

SYNTAX

status = ENTER_SCR ();

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

// get exclusive access to the processor

if (status = ENTER_SCR () == SUCCESS)

{

exclusive_action();

status = EXIT_SCR (); // release exclusive access

}

else

{

alternate_action(); // wait or alternate processing

}

}

DESCRIPTION

Get mutually exclusive access to the processor.

This primitive is implemented by disabling maskable interrupts and is not associated with a particular resource. Access is released by EXIT_SCR.

This primitive is recommended for mutually exclusive access of short duration because kernel time-related function is affected.

The processor condition code register is preserved upon return from the EXIT_SCR primitive.

This is a non-suspending primitive.

PARAMETERS

none

RETURN

none

ENTER_SSTATE

Enter Supervisory State

SYNTAX

ENTER_SSTATE ();

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int int0(void)

{

ENTER_SSTATE (); // enter supervisory state

handle_interrupt0() // interrupt processing

EXIT_SSTATE (); // return to previous state

}

DESCRIPTION

This primitive is the mechanism for an interrupt service routine to invoke supervisory state processing.

This primitive allows the calling interrupt service routine and nested interrupt service routines to switch to the common system stack.

The last interrupt service routine to exit the supervisory state returns control to the interrupted task and switches to the task stack.

For every ENTER_SSTATE call, there must be a matching EXIT_SSTATE call.

PARAMETERS

none

RETURN

none

EXIT_CR

Release Access to Resource

SYNTAX

status = EXIT_CR (cr_id);

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

BYTE app_cr;

// get critical region ID defined in config file

if (GET_CRID (RESOURCE_A, &app_cr) == SUCCESS)

{

status = ENTER_CR (&app_cr);

switch (status):

{

case SUCCESS: // region acquired

process_resource();

status = EXIT_CR (&app_cr); // release region

break;

default:

case FAILURE: // invalid cr ID

LOG_WARN (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_L + P0 + 0, NOT_USED);

}

}

}

DESCRIPTION

Release control of a resource that was acquired with the ENTER_CR primitive.

The resource identifier must first be gotten using the CR_GETID primitive and must be the same identifier used to acquire the resource with ENTER_CR. Only the task that currently has access to the resource may unlock the resource.

When the resource is released, if a higher-priority task is waiting on the resource, the current task is suspended, and the higher-priority task becomes the active task. The suspended task becomes active according to its assigned priority.

An error status is returned if the resource wasn’t previously locked, an invalid resource id was given, or corrupted data structures were detected.

PARAMETERS

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cr_id | BYTE* | Resource id |

RETURN

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| SUCCESS | Resource released. |

| FAILURE | Invalid resource id, resource not acquired with previous ENTER_CR by this task, or corrupted kernel data detected. |

EXIT_SCR

Release Exclusive Access to Processor

SYNTAX

status = EXIT_SCR ();

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

// get exclusive access to the processor

if (status = ENTER_SCR () == SUCCESS)

{

exclusive_action();

status = EXIT_SCR (); // release exclusive access

}

else

{

alternate_action(); // wait or alternate processing

}

}

DESCRIPTION

This primitive is the complement of ENTER_SCR and releases mutually exclusive control of the processor.

The processor condition code register at the time ENTER_SCR was called is restored.

This primitive must not be called without a previous call to ENTER_SCR.

PARAMETERS

none

RETURN

none

EXIT_SSTATE

Exit Supervisory State

SYNTAX

EXIT_SSTATE ();

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int int0(void)

{

ENTER_SSTATE (); // enter supervisory state

handle_interrupt0() // interrupt processing

EXIT_SSTATE (); // return to previous state

}

DESCRIPTION

This primitive complements the ENTER_SSTATE primitive and returns to the task state from the supervisory state.

For every ENTER_SSTATE call, there must be a matching EXIT_SSTATE call.

Interrupts may be nested and ENTER_SSTATE primitive calls may be nested. If EXIT_SSTATE is called by an interrupt service routine that isn’t the last interrupt service routine pending, processing continues in the supervisory state.

The last interrupt service routine to exit the supervisory state returns control to the interrupted task and switches to the task stack.

PARAMETERS

none

RETURN

none

GET_CRID

Get Resource Identifier

SYNTAX

status = GET_CRID (cr_name, crid_p);

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

BYTE app_cr;

// get critical region ID defined in config file

if (GET_CRID (RESOURCE_A, &app_cr) == SUCCESS)

{

status = ENTER_CR (&app_cr);

switch (status):

{

case SUCCESS: // region acquired

process_resource();

status = EXIT_CR (&app_cr); // release region

break;

default:

case FAILURE: // invalid cr ID

LOG_WARN (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_L + P0 + 0, "Region doesn't exist");

}

}

}

DESCRIPTION

This primitive gives a resource's identifier given the resource's name.

The identifier is used for the ENTER_CR and EXIT_CR primitives, which allow mutually exclusive access to the resource.

Resource names are assigned in the system configuration file. The name is a consecutive number, beginning with zero and ending with one less than the number of resources allocated. Designers may define literals to associate more meaningful names with a resource.

The name is used by this primitive to map to the semaphore data structures associated with the resource, however, these data structures never need to be referenced by an application.

Because a resource identifier doesn’t change once it is created by the kernel, this primitive only needs to be called once.

This is a non-suspending primitive.

PARAMETERS

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cr_name | INT | Resource name |

| crid_p | BYTE* | Resource id location |

RETURN

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| SUCCESS | Resource id available. |

| FAILURE | Invalid resource name. |

GETMYTID

Get Own Task Identifier

SYNTAX

status = GETMYTID (tid_pp);

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

TID *tid_p;

status = GETMYTID (&tid_p); // get id of this task

switch (status):

{

case SUCCESS: // valid task id

this_task_handler();

break;

default: // system fault

case FAILURE:

LOG_FATAL (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_L + P0 + 0, NOT_USED);

}

}

DESCRIPTION

This returns the identity of the currently active task. It operates the same as GETTID, except the task name isn’t needed.

The task that invokes this primitive is the currently active task.

This primitive also verifies the integrity of the task's data structures.

Because the task's identity doesn’t change after it is created, this primitive only needs to be called once.

This is a non-suspending primitive.

PARAMETERS

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| tid_pp | BYTE** | Task id location |

RETURN

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| SUCCESS | Task id available. |

| FAILURE | Task data structure fault detected. |

GETTID

Get Task Identifier

SYNTAX

status = GETTID (tname, tid_pp);

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

TID *tid_p;

CHAR test_msg[];

status = GETTID (TASK_0, &tid_p); // get id of given task

switch (status):

{

case SUCCESS: // valid task id

test_msg = "This is a test."

status = SEND (*tid_p, TEST_MSG_ID, &test_msg, sizeof(test_msg));

break;

default:

case FAILURE: // invalid task name

LOG_WARN (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_L + P0 + 0, NOT_USED);

}

}

DESCRIPTION

This primitive is used to get a task's identifier, which is used with other primitives that reference a task.

Given a logical task name, defined at compile time, this primitive returns the run-time identity of the task.

The task name is a number between zero and the maximum allowed number of tasks, minus one. The maximum number of tasks in the GX/kernel is 64. The task name is assigned in the configuration file.

The task identifier is a pointer variable to the task's control data structure, however, the application never needs to reference the data structure in normal operation.

The task must exist in the kernel's task data area. The task may not exist if this primitive is called from a procedure before tasks are created or if the task was terminated as a result of an error detected by the kernel. In these cases, INV_ADDR is returned as the task identifier.

Because a task's identity never changes once it is created, this primitive only needs to be called once, usually during initialization.

This primitive also checks the task's data structures for consistency.

This is a non-suspending primitive.

PARAMETERS

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| tname | CHAR | Task logical name. |

| tid_pp | BYTE** | Task id location. |

RETURN

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| SUCCESS | Task id available. |

| FAILURE | Invalid task name, task doesn’t exist, or invalid data. |

GETTIK

Get Current System Timer Value

SYNTAX

status = GETTIK (tikval_p)

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

WORD tikval_p;

if (GETTIK (&tikval_p) == SUCCESS) // get timer tik

{

process_tik()

}

else

{

LOG_FATAL (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_L + P0 + 0, NOT_USED);

}

}

DESCRIPTION

Get the current system time counter value.

The value is a continuous, 16-bit, 100-millisecond counter.

PARAMETERS

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| tikval_p | WORD* | Current timer value location. |

RETURN

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| SUCCESS | Timer value available. |

| FAILURE | Kernel fault. |

LOCATE_MEM

Locate Task Dynamic Memory

SYNTAX

status = LOCATE_MEM (mem_pp);

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

CHAR *mem_pp;

status = LOCATE_MEM (mem_pp); // get task dynmem address

switch (status):

{

case SUCCESS: // memory available

memory_action();

break;

default:

case FAILURE: // mem not allocated for task

LOG_WARN (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_L + P0 + 0, NOT_USED);

}

}

DESCRIPTION

Get the location of a dynamic memory partition allocated to the current task.

This memory partition is never used by the kernel, unlike the tasks' stack area, and is only made known to the task assigned to the partition. Once the task locates its memory, there are no restrictions on its use and it may be made available to other tasks.

This primitive only needs to be called once, preferably at task initialization time.

Higher-level memory management functions are the responsibility of the task; memory is never released through the kernel.

The memory is defined in the configuration file, by specifying the memory size needed by the task. The requested size is guaranteed to the task at run-time, although the location is determined by the kernel from available memory.

PARAMETERS

| Name | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| mem_pp | CHAR** | Address for task's dynamic memory location. INV_ADDR is returned if memory hasn’t been allocated for the task. |

RETURN

| Value | Description |

|---|---|

| SUCCESS | Memory location available. |

| FAILURE | Memory not allocated for task. |

LOG_FATAL

Indicate Fatal Fault Occurrence

SYNTAX

status = LOG_FATAL (loc, qual);

#include <gxos.h>

#include <gxconfig.h>

int main(void)

{

WORD tikval_p;

if (GETTIK (&tikval_p) == SUCCESS) // get timer tik

{

process_tik()

}

else

{ // report location of fatal fault with info

LOG_FATAL (LY_0 + SS_0 + LV_L + P0 + 0, "System error");

}

}

DESCRIPTION

Log fatal-type fault and initiate recovery.

If a task has been defined in the configuration file as a fault handler, the task is signaled with EVT_0, to indicate a fatal fault occurred, provided the fault didn’t occur in the fault handler task.

If a task detects and reports a fatal-type fault or the kernel detects a fatal-type fault in the task domain, the task is removed from the list of available tasks and is never scheduled to run again. In this case, this primitive returns to the scheduler and the system continues to run, as much as possible without the affected task.

If a fatal-type fault is detected in the kernel domain or in hardware on which the kernel is dependent, system integrity can’t be guaranteed and a STOP instruction is executed. Upon reset, the fault is signaled to the fault handler task, if one was defined.

In all cases, fault-related information is logged to the fault analysis area for future reference. This includes fault location, fault-specific data, task and kernel stack areas, and kernel and task states. These data are preserved until the next fault, even through a system reset.

PARAMETERS

| Name | Type | Description | | — | — | — |arn | loc | WORD | location code | | qual | WORD | Fault qualifier |

RETURN

Not applicable

LOG_WARN

Indicate Non-fatal Fault Occurrence

SYNTAX